Meiyan LI

Chinese Attorney-at-Law

Beijing Wei Chixue Law Firm

Chinese Attorney-at-Law

Beijing Wei Chixue Law Firm

Article 10 of the Trademark Law outlines the signs that cannot be used as trademarks. In recent years, there has been a notable increase in cases where trademark applications were rejected for violating these prohibited provisions. A large portion of these rejections arises from violations of Article 10(i)(7) and (8), which prohibit trademarks that “are deceptive and are likely to mislead the public in terms of the quality, place of production, or other characteristics of the goods” and those that are “detrimental to socialist ethics or customs, or have other unwholesome influences”. In practice, we frequently receive inquiries from applicants about whether trademarks rejected under Article 10 can continue to be used. This article will provide an overview of review of refusal cases related to Article 10, the relevant legal provisions, and actual enforcement cases to illustrate the practical risks of using trademarks that have been rejected for violating prohibited provisions.

1. Statistical Analysis of Review of Refusal Cases Involving Article 101

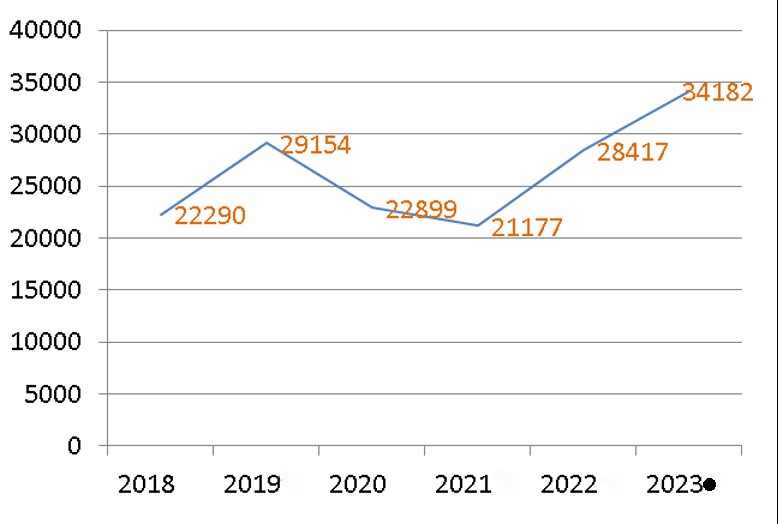

According to the Mozlen database search, the number of decisions in review of refusals involving Article 10 is shown in the chart below. Following a brief decline in 2020 and 2021, the number of cases has steadily increased, reaching 34,182 in 2023, accounting for 14.6% of the total refusal review decisions for that year.

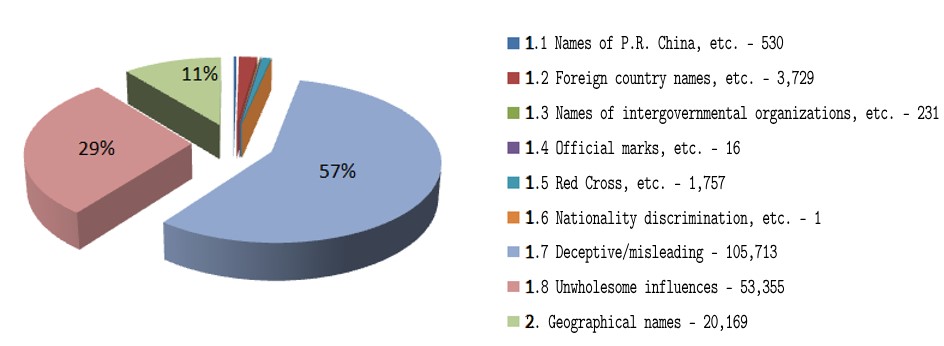

According to the search results of review decisions related to Article 10, the proportions of cases involving specific items (i.e., Article 10(i)(1) to (8) and Article 10(ii)) are as follows: cases involving Article 10(i)(7) amounted to 105,713, accounting for as much as 57%, while cases involving Article 10(i)(8) amounted to 53,355, accounting for 29%.

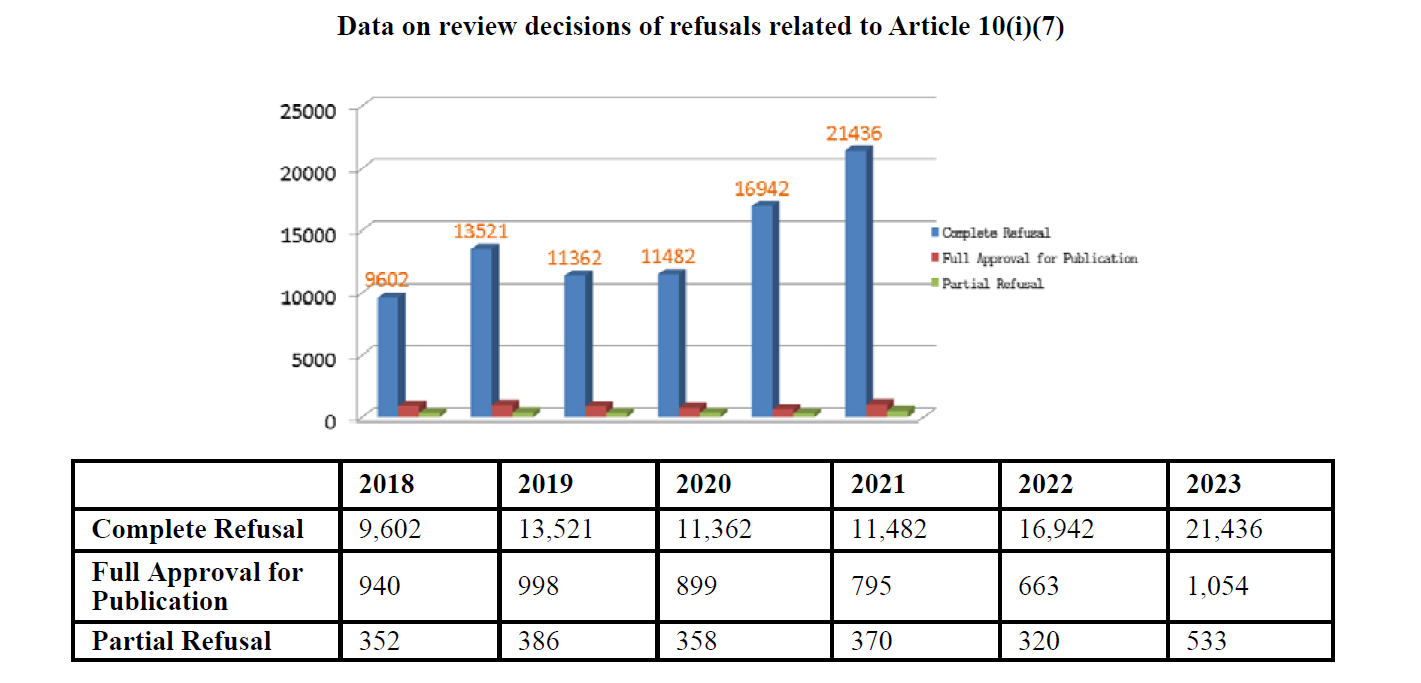

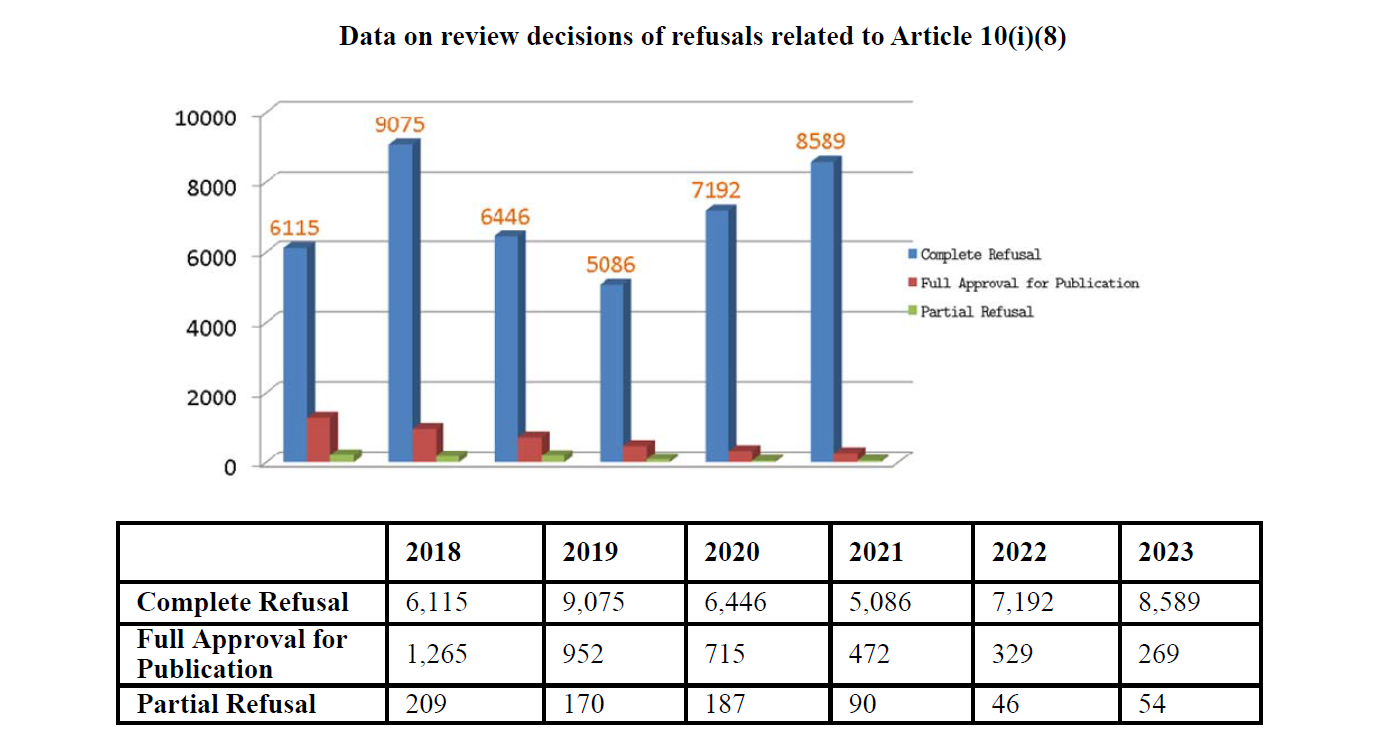

In contrast, among the review decisions involving Article 10(i)(7) or (8), the outcome of “complete refusal” accounted for the largest proportion, followed by “full approval for publication”, with “partial refusal” being the least common. This indicates that for trademarks rejected under Article 10(i)(7) or (8), even if a review is applied for, the chances of the trademark being approved for publication remain low.

2. Penalties for Using Prohibited Marks

According to Article 52 of the Trademark Law, “Where a party passes off an unregistered trademark as a registered trademark or uses an unregistered trademark in violation of Article 10 of this Law, the relevant local administrative department for industry and commerce shall stop such acts, order the party to make correction within a time limit, and may circulate a notice on the matter. If the illegal business revenue is RMB 50,000 yuan or more, a fine of up to 20% of the illegal business revenue may be imposed; if there is no illegal business revenue or the illegal business revenue is less than RMB 50,000 yuan, a fine of up to RMB 10,000 yuan may be imposed.” Furthermore, Article 15 of the “General Criteria for Determining Trademark Violations” issued by the China National Intellectual Property Administration (CNIPA) (Notice No. 34 [2021], hereinafter referred to as “Determination Criteria”) specifies: “If the CNIPA determines that a trademark registration application violates the provisions of Article 10 of the Trademark Law and the relevant decision or ruling has taken effect, any continued use of the trademark by the applicant or others shall be dealt with by the trademark enforcement department in accordance with the law.”

According to Article 5 of the “Determination Criteria”, whether the use of an unregistered trademark violates Article 10 of the Trademark Law is generally judged based on the common understanding of the public within China. However, an exception is made if there is reasonable and sufficient evidence to prove that a specific group within the Chinese public believes the use of the unregistered trademark to violate Items 6 to 8 of Article 10(i). Articles 6 to 14 of the “Determination Criteria” further specify the detailed criteria for determining violations related to Article 10 of the Trademark Law.

Based on the above provisions, the use of trademarks that violate Article 10 of the Trademark Law can be divided into two types. The first type involves the use of trademarks that have not been registered, meaning they have not been previously rejected. The risks associated with this situation can be specifically assessed according to the relevant provisions of the Trademark Law and the criteria set forth in the “Determination Criteria”, combined with the actual circumstances of use. The second type concerns the use of trademarks that have applied for registration but were rejected. For this situation, according to Article 15 of the “Determination Criteria”, once the relevant decisions or rulings have come into effect, the trademark applicant or others must cease using the trademark in question; otherwise, the trademark enforcement departments may investigate and penalize the trademark use. The author believes that Article 15 of the “Determination Criteria”, which considers the effectiveness of relevant rulings as the criterion for determining legality, serves as a strong guide in actual enforcement practices. However, in essence, the object of investigation by the trademark enforcement department is the conduct that violates Article 10 of the Trademark Law. Therefore, determining a violation of Article 10 should focus on the actual usage behavior of the trademark itself, rather than whether the relevant ruling has taken effect. For example, in trademark practice, the assessment of trademark similarity during the authorization and confirmation stage is often stricter than during the civil infringement stage. When evaluating the actual use risk of a trademark that was rejected due to the existence of a prior trademark, factors such as the reputation and distinctiveness of the prior trademark, the actual usage circumstances of the disputed trademark, and the intent of the user are considered, with a comprehensive judgment ultimately based on whether it is likely to cause confusion or misidentification among the relevant public. As mentioned above, the review and determination process for Article 10 has tightened in recent years. Moreover, due to the influence of examiner’s subjective judgments and various conditions, such as the timing and evidence available during trademark examination, some trademarks rejected under Article 10 may not necessarily be deemed violations in practical scenarios, especially those concerning Article 10(i)(7).

For example, In the retrial of case (2019) No. 249 by the Supreme People’s Court, the CNIPA believed that the trademark “肾源春冰糖蜜液 (Shen Yuan Chun Bing Tang Mi Ye)” could be understood as “a liquid beneficial to the kidneys, brewed with rock sugar and honey”. When such a trademark is used on designated products like medicinal wine, it could easily mislead consumers about the ingredients and characteristics of the product. However, the Supreme Court held that, based on the general public’s common understanding, the terms “冰糖 (Bing Tang)” and “蜜 (Mi)” in the trademark indicate that the product contains “rock sugar” and “honey”. According to the evidence submitted by the applicant, the product using the applied trademark indeed includes rock sugar and honey in its formulation. Therefore, based solely on the trademark itself, it is insufficient to conclude that using the trademark on the designated products would mislead the relevant public about the ingredients or characteristics of the product. It is difficult to establish that it constitutes deception of the public. Consequently, the court determined that using the applied trademark on the specified products does not violate Article 10(i)(7) of the Trademark Law. In other words, if the trademark applicant had not persisted with the litigation to the end, the CNIPA’s refusal notification would have become effective, and the continued use of the trademark would have been subject to penalties.

Therefore, the author believes that, in practice, the statement “if the CNIPA determines that a trademark application violates the provisions of Article 10 of the Trademark Law and the relevant decision or ruling has taken effect” should not be simply equated with “the use of an unregistered trademark in violation of Article 10 of the Trademark Law”. As the “Determination Criteria” serves as a guiding document for trademark enforcement departments, enforcement personnel will still investigate and penalize such trademark usage according to Article 15 of the “Determination Criteria” when they identify the aforementioned second type of trademark usage. If the party involved believes that the trademark in use does not actually fall under the circumstances specified in Article 10 of the Trademark Law, they can initially provide relevant evidence to argue that it does not fall within the prohibited conditions. If they are still penalized, they may consider filing an administrative lawsuit or administrative review in accordance with the Administrative Litigation Law and the Administrative Reconsideration Law to challenge the punitive action while also requesting an incidental review of the regulatory document. However, the likelihood of approval is quite low.

3. Introduction to Investigation Cases

In light of the above legal provisions, continuing to use trademarks rejected for violating Article 10 of the Trademark Law after the relevant decision or ruling has taken effect carries the risk of investigation and fines. This raises an important question: will the trademark enforcement departments conduct targeted inspections on such rejected trademarks?

The author notes that in June 2018, the General Office of the State Administration for Market Regulation issued a notice regarding the “Special Action Plan for the ‘Purification’ Campaign to Combat the Use of Unregistered Trademarks Violating the Prohibited Provisions of the Trademark Law” 2. According to the plan, the campaign was structured into four stages: lead investigation, mobilization and deployment, coordinated implementation, and summary and closure. The Trademark Office of the CNIPA searched the trademark database and compiled a list of trademark registration applications that had been rejected since 2017 for violations of Article 10 of the Trademark Law, forming the investigation list for the campaign. The author was unable to locate the investigation list or the summary report for this special campaign. However, according to news reports from several local regulatory departments, none of these departments identified instances of applicants using trademarks that had been rejected for violating the prohibited provisions. Additionally, no reports were found indicating that market regulatory departments have conducted similar campaigns since then. Nevertheless, the author believes that, compared to routine supervision by trademark enforcement departments, conducting supervision through special campaigns offers greater structure and operational feasibility.

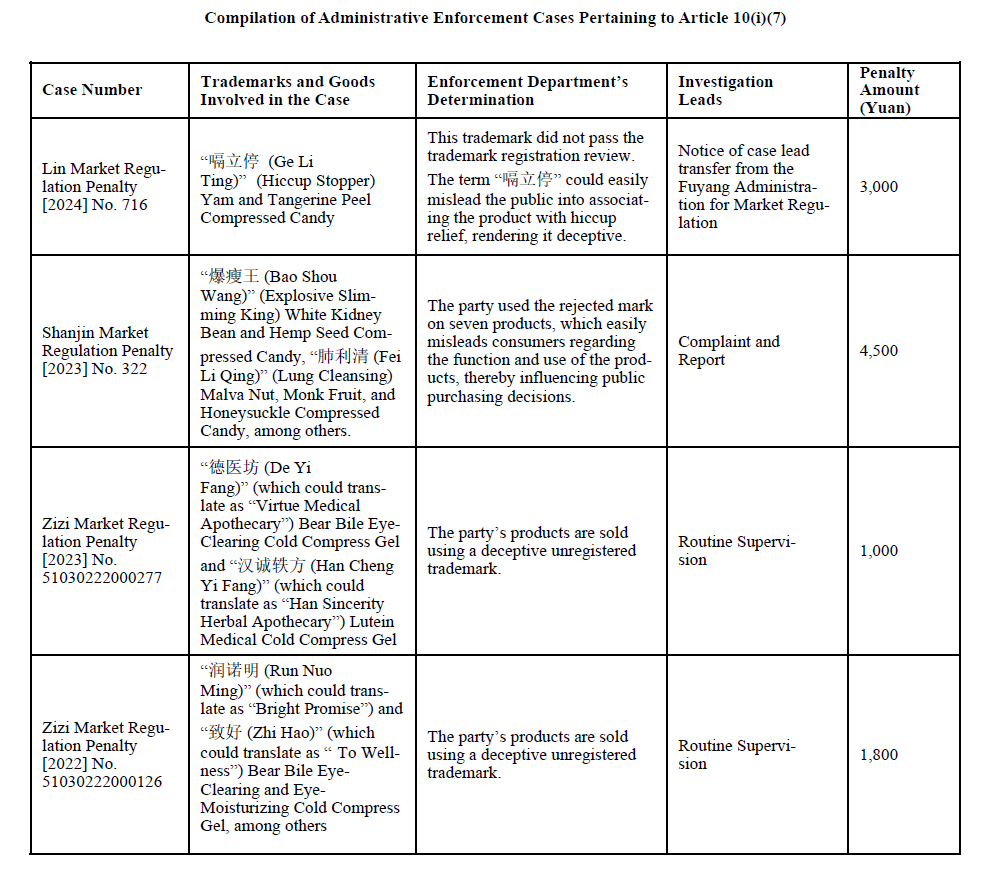

Regarding actual investigated and penalized cases, as mentioned earlier, trademarks rejected under Article 10(i)(7) and (8) represent the largest proportion. This article will introduce relevant penalty cases related to these two items. Using the Wolters Kluwer Legal Information Database3, cases of administrative regulation were searched with “Trademark Law Article 10(i)(7)” and “Trademark Law Article 10(i)(8)” as keywords. As of the time this article was written, twenty-seven cases were found under “Article 10(i)(7)” and one hundred and twenty-five cases under “Article 10(i)(8)”, including some cases not directly related to these two Items. This data may only represent the tip of the iceberg in terms of actual cases, but it is clear that, both in terms of penalty amounts and case numbers, enforcement is stricter for violations under Article 10(i)(8) compared to those under Item 7. A selection of representative penalized cases has been compiled, summarizing the trademarks involved, penalty amounts, and official findings for reference.

The above cases indicate that penalties for trademarks violating Article 10(i)(7) are primarily due to the misleading nature of the trademarks, which causes consumers to misunderstand the efficacy of the products. Penalty amounts are generally around several thousand yuan, though the fines are closely related to the scale of the illegal business operations. Most penalized entities in these cases are distributors with likely limited inventory, which may account for the relatively low penalty amounts.

Among the 125 cases involving Article 10(i)(8), as many as 45 cases, or 36%, were penalties related to the “特种兵” (Special Forces) mark. Notably, in June 2022, six departments, including the Logistic Support Department of the Central Military Commission, issued a “Notice on Prohibiting the Sale of ‘Military’-Branded Tobacco and Alcohol Products”, which explicitly mandates “a strict ban on the online and offline sale of ‘military’-branded tobacco and alcohol products” and “close regulation of ‘military’-branded tobacco and alcohol products”. This may explain the intensified crackdown on products using the “Special Forces” mark since 2022. In terms of penalties, fines for using the “Special Forces” mark generally range around several hundred yuan, with cases reaching several thousand or even ten thousand yuan being relatively rare.

Additionally, there were as many as 25 penalty cases, or 20%, involving suspected mala fide applications. These applications not only include names associated with national leaders or Olympic champions, such as “瓶净悉净瓶 (Ping Jing Xi Jing Ping)”, “PUTIN”, “陈梦 (Chen Meng)”, and “Quanhongchan 全红婵”, but also trademarks like “雷神山 (Leishenshan)” and “火神山 (Huoshenshan)”, symbolizing the Chinese people’s determination to win the battle against the pandemic. Furthermore, they include trademarks such as “叫了个鸡 (Called a Chicken)”, which briefly became a topic due to its vulgar connotations. For these mala fide applications, even if the trademarks were not put into use, trademark enforcement departments penalize the applicants based on directives from higher authorities or provided leads. According to the cases retrieved, penalties generally range around several thousand yuan. Penalties for cases involving national leaders or those with significant negative impact are relatively higher, often reaching tens of thousands of yuan. The higher penalty in the third example above reflects not only the negative social impact but also the high value of the goods involved.

Furthermore, leads for enforcement actions involving Article 10(i)(7) and (8) can be classified into three conditions. The first is when trademark enforcement departments conduct inspections in response to complaints and reports. The second is when these departments carry out nationwide special campaigns targeting rejected trademarks or conduct focused inspections of applicants based on directives from higher authorities. The third is routine supervision by trademark enforcement departments. Based on the “Notice” referenced above and the types of cases investigated, it is clear that the current focus of trademark enforcement is on the use of military designations as trademarks in sectors such as tobacco, alcohol, and beverages.

4. Conclusion

First and foremost, it should be clarified that, regardless of whether a trademark has been previously rejected due to prohibited provisions, there remains a risk of investigation and penalty if the trademark enforcement departments deem the unregistered trademark to fall under the provisions of Article 10 of the Trademark Law. For unregistered trademarks that were previously rejected and have effective rulings, trademark enforcement departments may conduct targeted inspections of the relevant entities based on special campaigns, directives from higher authorities, or third-party reports.

In cases investigated for violating prohibited provisions, enforcement is generally stricter for violations of Article 10(i)(8) compared to Article 10(i)(7). For mala fide applications involving trademarks identical or similar to the names of domestic or foreign leaders or Olympic champions, there is a risk of penalty from trademark enforcement departments, even if the trademarks were not used. Additionally, if a trademark includes politically sensitive terms, such as “Special Forces” or “Qiushi”, the risk of investigation is very high, with limited room for defense. For trademarks rejected under Article 10(i)(7), enforcement cases suggest that the primary reason is that the trademark can easily lead consumers to misinterpret the product’s efficacy. Regarding the assessment of whether the public would be misled about product quality or other characteristics, the author believes that rejection at the trademark authorization and confirmation stage under Article 10(i)(7) does not necessarily mean that actual use would mislead the public about the product’s quality. However, given current enforcement practices, continued use of a rejected trademark still carries a risk of investigation.

Finally, with the continuous increase in the number of trademarks rejected for violating prohibited provisions under Article 10, similar rejections are likely to rise in the future. If a rejected trademark is crucial to the applicant and they believe its actual use would not mislead the public or have unwholesome influences, it is advisable to fully utilize review procedures or even administrative litigation to seek registration approval. In practice, prohibited provisions can sometimes be challenging to overcome. Therefore, if the refusal decision is final, abandoning the use of the relevant trademark remains the safest option. If there is a strong necessity to use a rejected trademark, a comprehensive assessment should be conducted based on the specific circumstances of the trademark’s use, evaluating the likelihood of investigation and penalty by the trademark enforcement departments and the potential legal liabilities, before making a final decision.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————Additionally, there were as many as 25 penalty cases, or 20%, involving suspected mala fide applications. These applications not only include names associated with national leaders or Olympic champions, such as “瓶净悉净瓶 (Ping Jing Xi Jing Ping)”, “PUTIN”, “陈梦 (Chen Meng)”, and “Quanhongchan 全红婵”, but also trademarks like “雷神山 (Leishenshan)” and “火神山 (Huoshenshan)”, symbolizing the Chinese people’s determination to win the battle against the pandemic. Furthermore, they include trademarks such as “叫了个鸡 (Called a Chicken)”, which briefly became a topic due to its vulgar connotations. For these mala fide applications, even if the trademarks were not put into use, trademark enforcement departments penalize the applicants based on directives from higher authorities or provided leads. According to the cases retrieved, penalties generally range around several thousand yuan. Penalties for cases involving national leaders or those with significant negative impact are relatively higher, often reaching tens of thousands of yuan. The higher penalty in the third example above reflects not only the negative social impact but also the high value of the goods involved.

Furthermore, leads for enforcement actions involving Article 10(i)(7) and (8) can be classified into three conditions. The first is when trademark enforcement departments conduct inspections in response to complaints and reports. The second is when these departments carry out nationwide special campaigns targeting rejected trademarks or conduct focused inspections of applicants based on directives from higher authorities. The third is routine supervision by trademark enforcement departments. Based on the “Notice” referenced above and the types of cases investigated, it is clear that the current focus of trademark enforcement is on the use of military designations as trademarks in sectors such as tobacco, alcohol, and beverages.

4. Conclusion

First and foremost, it should be clarified that, regardless of whether a trademark has been previously rejected due to prohibited provisions, there remains a risk of investigation and penalty if the trademark enforcement departments deem the unregistered trademark to fall under the provisions of Article 10 of the Trademark Law. For unregistered trademarks that were previously rejected and have effective rulings, trademark enforcement departments may conduct targeted inspections of the relevant entities based on special campaigns, directives from higher authorities, or third-party reports.

In cases investigated for violating prohibited provisions, enforcement is generally stricter for violations of Article 10(i)(8) compared to Article 10(i)(7). For mala fide applications involving trademarks identical or similar to the names of domestic or foreign leaders or Olympic champions, there is a risk of penalty from trademark enforcement departments, even if the trademarks were not used. Additionally, if a trademark includes politically sensitive terms, such as “Special Forces” or “Qiushi”, the risk of investigation is very high, with limited room for defense. For trademarks rejected under Article 10(i)(7), enforcement cases suggest that the primary reason is that the trademark can easily lead consumers to misinterpret the product’s efficacy. Regarding the assessment of whether the public would be misled about product quality or other characteristics, the author believes that rejection at the trademark authorization and confirmation stage under Article 10(i)(7) does not necessarily mean that actual use would mislead the public about the product’s quality. However, given current enforcement practices, continued use of a rejected trademark still carries a risk of investigation.

Finally, with the continuous increase in the number of trademarks rejected for violating prohibited provisions under Article 10, similar rejections are likely to rise in the future. If a rejected trademark is crucial to the applicant and they believe its actual use would not mislead the public or have unwholesome influences, it is advisable to fully utilize review procedures or even administrative litigation to seek registration approval. In practice, prohibited provisions can sometimes be challenging to overcome. Therefore, if the refusal decision is final, abandoning the use of the relevant trademark remains the safest option. If there is a strong necessity to use a rejected trademark, a comprehensive assessment should be conducted based on the specific circumstances of the trademark’s use, evaluating the likelihood of investigation and penalty by the trademark enforcement departments and the potential legal liabilities, before making a final decision.

1 The data in this section is sourced from the Mozlen database (https://home.mozlen.com/), and the tables are compiled by the author.

2 https://sbj.cnipa.gov.cn/sbj/tzgg/201807/W020180711559602549716.pdf

3 https://law.wkinfo.com.cn